- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

By Georges!

A new Brussels museum launches with a show evoking the long life, immoderate times and prodigious productivity of Georges Simenon

Any time Belgians are inspired to celebrate themselves I am eager to join them. They don’t do it often enough. But now Brussels has made up for a serious absence in its cultural profile; it has installed a handsome Museum of Letters and Manuscripts in the grand 19th-century royal galleries of Saint Hubert. True, it’s only a short downhill stroll from the royal Albert I library, which is a world-famous repository of invaluable books and documents, but who goes there? That estimable, mid-20th-century edifice attracts scholars; only rarely is it explored by the casual visitor. The new museum is a different story altogether.

It must be acknowledged that the initiative for this admirable venture has come to us from Paris. Aristophil is a private French organisation devoted to the collection and conservation of rare documents. It has a Belgian affiliate that carries on similar activities, authenticating and preserving everything from menus to musical scores. The Belgian MLM, as it’s known, is the sister institution of the museum of the same name set up by Aristophil in Paris in 2004. The two museums share and exchange the manuscripts, periodicals and papers of every sort (at last count, some 80,000 in all), many of them related to the history or literary production of France and Belgium.

The first of what will be a year-round series of exhibitions in Brussels looks back as far as the 16th century, the era of Charles V, with some of the earliest anatomical illustrations by Brussels-born Andreas Vesalius. We then race through the centuries, taking in the Brabançonne Revolution of 1789 along the way and, after 1830, the new nation’s kings and queens.

The small well-lit rooms are laid out with glass-topped cases featuring letters, backs of envelopes and scraps of paper with notes or sketches on them by Belgian or visiting writers and artists. Side by side in less than strictly chronological order are original mementoes of Delacroix, Monet and Picasso as well as our own Ensor and Magritte. Tintin’s creator, Hergé, is there, of course, and Flanders’ finest writer, Hugo Claus.

When Albert Einstein fled Nazi Germany in 1933, he was invited to Laeken by Queen Elisabeth (both amateur violinists, they played in an improvised string quartet). Letters from the famous refugee are included in the section dedicated to science. The nearby music section includes drafts of songs by Jacques Brel.

Navigating the crowded exhibitions is made easier by several digital displays that allow you to turn pages of rare manuscripts at the touch of a button. There are the usual headphones with further information in French, Dutch or English.

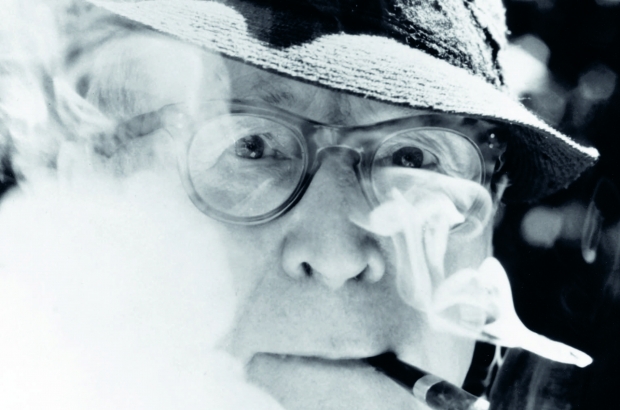

The museum’s first special exhibition dedicated to a single Belgian author concentrates on the notoriously prolific Liège-born novelist Georges Simenon. Far too much has been made of the enormous size of his literary output and not enough of the quality. The usual numbers – the 117 so-called ‘non-Maigret’ books, the 84 ‘Maigrets’, the 21 dictées composed by talking his memoires into a microphone – tend to conceal the fact that Simenon is one of the major novelists of the 20th century. Recognition has come gradually, first with the inclusion of some 20 of his works in Editions Gallimard’s prestigious Pléiade library of authors from Balzac to Zola, and now with new translations of, so far, eight novels into English published as ‘classics’ by the New York Review of Books.

If Simenon has gained an unfair reputation as a literary lightweight it is simply because he allowed his name to become so closely associated with his police inspector protagonist Jules Maigret. Before the name of Simenon became internationally recognised, he churned out potboilers for a living under a variety of pen names, 17 in all: Georges Sim, Luc Dorsan, Gom Gut, even Ploum et Zette. He would write as many as eight short stories a day to be published in magazines with titles like Froufrou or Paris Flirt. If he only had used a pseudonym for his Maigrets, we would not now have Amazon asking, “Are you looking for something in our Mystery and Thriller Books department?” and then directing us to several of his most serious novels with no trace of that taciturn, pipe-smoking commissaire.

Pedigree is a deeply moving and revealing autobiographical account of Simenon’s early life growing up in Liège. Another, Dirty Snow, has been favourably compared by more than one critic to Camus’s The Stranger. The museum displays many pages of Simenon’s careful typewriting with only the occasional correction in his small, neat handwriting. We see the calendars he used to keep track of his progress, each day crossed out as he finished his allotted 70 or 80 pages between breakfast and dinner.

Book jackets from the novels and posters from the more than 60 films that Simenon’s novels have inspired line the museum’s exhibition space. Many of France’s best directors and actors have found his dramatic stories with their atmosphere of menace and suppressed passion irresistible cinematic material. One of the best is Le Chat with Jean Gabin and Simone Signoret.

And then there were the women. In a private conversation with Federico Fellini that promptly became very public, Simenon offhandedly estimated that in a long and active lifetime he’d ‘had’ something like 10,000 women. A figure impossible to audit, it was at once accepted as fact, adding yet another silly statistic to his unverifiable reputation. One of his wives said “he always exaggerated” and there were probably no more than one-tenth that many. To which one can only add, quand même...

Unlike many writers and artists who need to keep their heads in the clouds for inspiration, Simenon was a canny, down-to-earth businessman. He never had an agent, drew up all his own contracts with publishers and producers and could drive a hard bargain, nor did he hesitate to ditch one publisher for another whenever he could get a better deal.

The exhibition at the MLM does nothing to explain the Simenon ‘mystery’ or ‘enigma’, words used in the titles of two of the biographies that make a bold stab at providing answers, but with little success. The only way to appreciate Georges Simenon properly is to read him. Translated into several dozen languages, he is not hard to find. He died in 1989 at the age of 86, a very rich man and a celebrity who enjoyed the notoriety that surrounded his name. And yet at the height of his career he never let anything keep him for long from his daily task with his faithful Royal typewriter.

Simenon’s archives are held by the Centre of Georges Simenon Studies at the University of Liège.