- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Behind the scenes: the Bulletin observes Brussels surgeon Dr Guy-Bernard Cadière in action

Photographer Natalie and I don surgical scrubs and follow Dr Guy-Bernard Cadière (see our main interview with him here) to the main sprawl of Saint-Pierre, to observe the removal of an infected gallbladder. We walk through the emergency entrance just as an ambulance off-loads a knife wound victim accompanied by police. It’s a vivid reminder that this is a frontline city hospital. “On average, we receive one stabbing a day,” says Cadière.

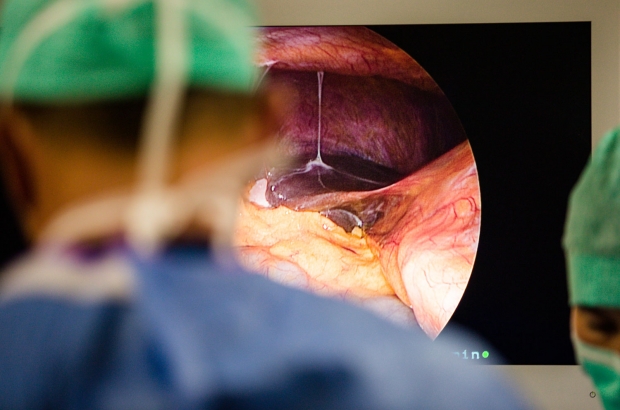

In the operating block we put on shoe covers, mask and cap and are told not to touch any part of the patient’s body; otherwise we have free access. Cadière is clearly in his element. A colleague has barely attached the ties of his gown before he gets down to business. The patient is under general anaesthetic, his stomach is exposed, shaved and disinfected, while the sound of his heart rate beeps in the background. An octopus-like apparatus surrounds him: tall columns with movable video screens and other equipment attached. In front of Cadière and his multinational team of three is one large screen with a high resolution 2D image, simultaneously broadcast to the other screens via the camera inside the stomach cavity. This is inflated by carbon dioxide.

At first glance, and with zero anatomical knowledge, it looks like a dramatic moonscape. We watch instruments enter the work space, foreign bodies piercing skin and tissue. There’s a pinching tool that carefully moves things around, and cutting and cauterising tools that delicately peel through the mass of fibrous tissue surrounding the gallbladder, which sits below the liver. Cadière works carefully, in continual discussion with his team. A burning smell accompanies the cauterising and Cadière instructs the anaesthetic team to increase coagulation to the patient to reduce blood loss. They are concentrated on their work, but the atmosphere is relaxed. Though continually in teaching mode, Cadière banters with the other surgeons, before he decides to dissect the cystic duct connecting the gallbladder to the common bile duct. The extent of the infected tissue has made it difficult to distinguish each organ, and there are individual variations in anatomy. Before it is cut, the duct is clipped, “three times to make sure we sleep at night”, says Cadière.

One of the trickiest parts is the removal of the redundant gallbladder. A plastic bag is introduced into the cavity; twice the organ is manoeuvred into it, but each time it breaks as the team try to extract it via one of the holes in the stomach. “The simplest thing would be to make an incision in the abdomen now,” says Cadière, but they persist until on the third attempt they succeed. “The team is very important in laparoscopy. You need to be able to trust the person holding the camera – they are your eyes,” Cadière explains. After a dramatic disinfection – iso-betadine is poured into the main hole and erupts as the CO2 is released, removing any residual debris with it. Each entrance point is then pinched and stapled. The patient will return home the next day, with his staples removed six days later.

There have been far more steps in the procedure than described here. While a routine operation, it still required a meticulous attention to detail. The operating theatre can also be a stage for creativity and ingenuity. Cadière likens surgical precision to abstract art or improvisation by a musician. “You aim to make the minimum of gestures in surgery,” he says. “It’s better for the patient, but it only comes from years of experience.”

Photos by Natalie Hill

This article was first published in the Bulletin Newcomer Autumn 2016